RESOURCES | PLAYBOOK

Intellectual property due diligence playbook (Founder)

This playbook helps ensure that the University can commercialise intellectual property (IP) from academic research, while also meeting the legal requirements. ‘IP’ here refers to a product or a process.

IP due diligence undertaken at the earliest stages of discovery helps ascertain whether the IP identified or disclosed by an inventor can be commercialised - typically either by spinning out a new company and granting it rights to the IP, or granting rights to the IP to an existing company via licensing, and so on.

This playbook is intended for technology transfer office (TTO) staff and academic researchers across all disciplines (SHAPE and STEM).

Key Points / Executive Summary

- Publishing or disclosing your research outputs can have knock-on effects for the commercialisation of your research. There are some critical aspects you need to consider and discuss with your TTO before you place anything in the public domain.

- IP can be protected and registered in a timely manner by your TTO, with no (or minimal) delay to publication or public disclosure.

- IP is owned by your employer (unless a contract says otherwise), and this ownership does not move when you change employment.

- In a competitive field, others may have existing IP. This does not necessarily exclude new related IP if it has a competitive advantage; your TTO will be able to map out the position.

- The research use exemption normally allows others to use for research purposes, thus generally patents do not limit research in a particular field (though in certain countries this exemption may be less defined).

- Understand any encumbrances on IP (such as joint ownership or needing funder consent to commercialise) and revenue sharing expectations, so that you are aware of these matters as they impinge on the commercialisation process

The Deal Readiness Toolkit

A short video introduction to the benefits of using the Deal Readiness Toolkit, covering a patent attorney perspective with insights from the Southampton TTO office

What is IP?

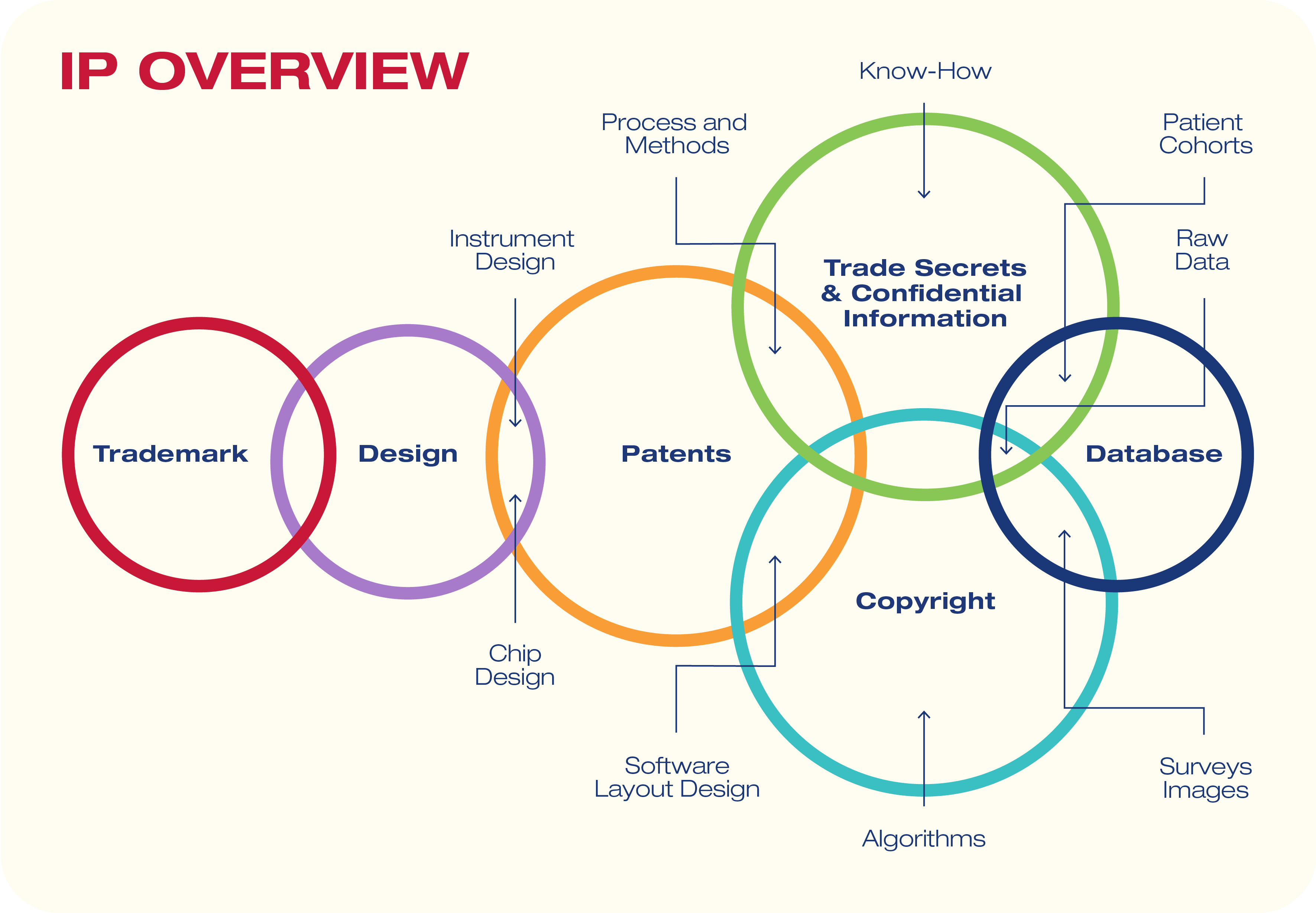

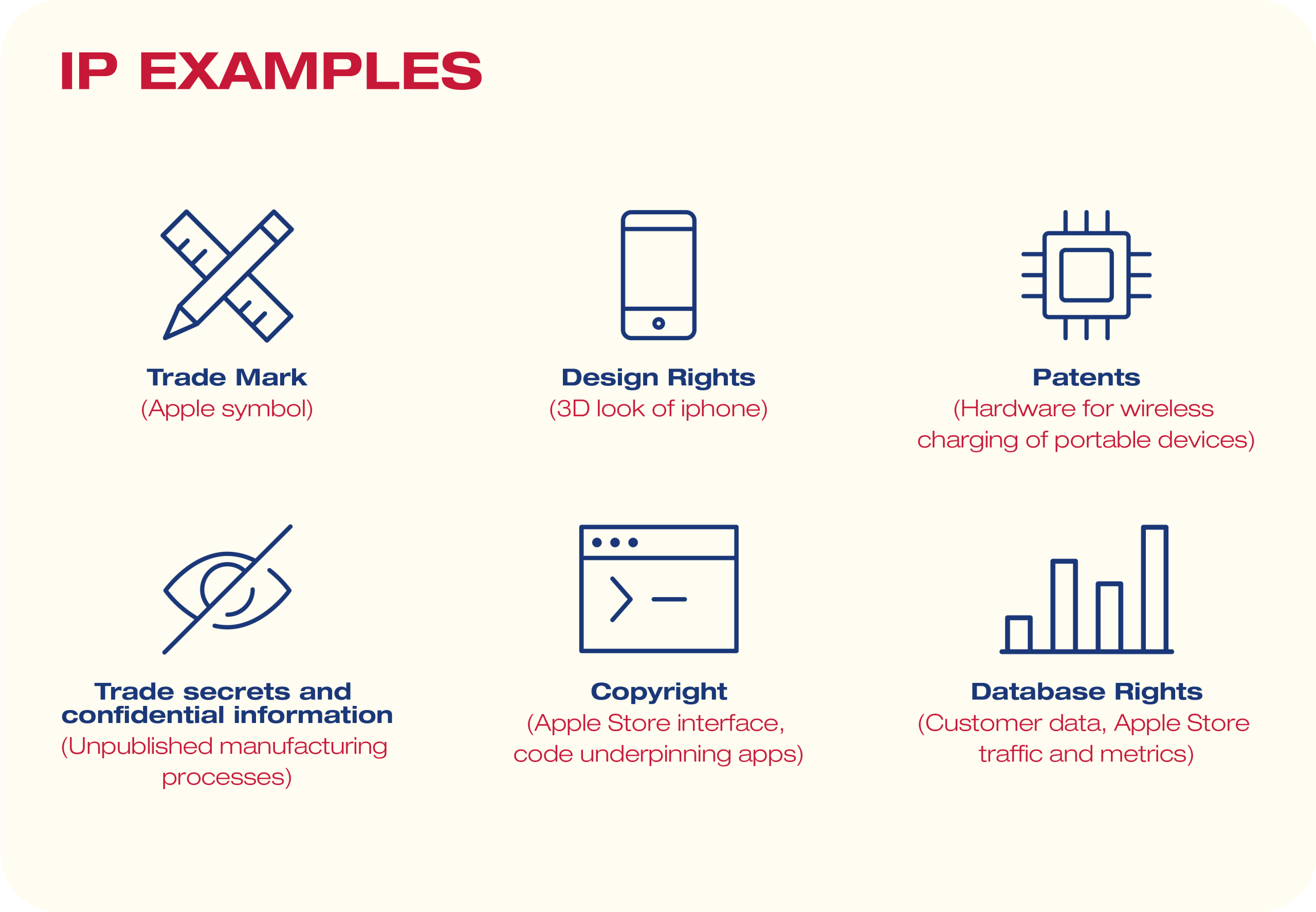

Intellectual property or ‘IP’ covers a product or process and falls into any of the six types of creative output developed within the University (see the diagram below).

[Used with permission of copyright owner, see examples below:]

Exploitable IP takes various forms. IP can be made available (by means of an agreed contract, typically a licence agreement) to others in a variety of ways, such as a freely available resource (e.g. some copyrighted materials or open-source software); or traded under a commercial licence (e.g. a patent claiming a new technology and its associated know-how), to a newly incorporated spin-out or an established entity.

What is IP due diligence?

The “innovation” needs to be assessed for its commercial viability, or its social value (if considering a social enterprise, in terms of its balance of an ESG profile). To do so, the University's TTO (or Research Innovation Services or Enterprise Division) needs to determine whether it is useful and whether there is a market for the innovation. Key questions to be answered at this stage are:

- What real-world problem does the invention solve?

- Is there a significant-sized market, and what is the value of the market?

- What would it take to commercialise (e.g. time, effort, cost, regulatory requirements, etc.)?

- Has the problem already been solved by someone else?

- Who are the potential licensees and customer base?

Its protectability needs to be ascertained: is the innovation novel and inventive, what is the ownership of the IP and are there any obvious encumbrances or (by undertaking a brief, targeted, novelty search). A more detailed freedom to operate (FTO) search can be undertaken at a later stage, usually in cooperation with a patent attorney, and if a commercially viable product has been determined. This is critical in enabling downstream commercialisation activities.

Why do we do IP due diligence?

Even if the main motivation for the IP is to obtain grant funding, the protection of a commercially viable and useful product or process needs to be demonstrated. If there is a commercial strategy, IP ownership needs to be concisely articulated prior to proceeding with protection for the innovation. If done successfully, TTO and academic could identify areas of future IP and new developments (both products and/or markets) to leverage more grant funding.

Why do we do IP due diligence?

We recommend you speak to your TTO in order for them to support you in the IP due diligence process. To help maximise the social benefits from your research by ensuring equitable rights for the creators of the IP, when the University and academic wishes to commercialise without infringing third-party rights.

Even when tensions and issues are identified, the commercial route can still be a viable one.

Being able to establish a recognisable commercial route and set out who owns what in the creation will result in a much smoother journey.

Errors in ownership or inventorship have the potential to give a third party or competitor a basis for a legal challenge to the protection or registration of the IP and render it invalid.

This is why ownership of IP must be clearly understood and agreed upon, given that it may be an asset accessed by a wide range of external stakeholders to yield impact.

If we fail to undertake IP due diligence, assuming the University owns the research outputs or not recognising third-party IP within our IP, this means we do not have the necessary rights to be able to commercialise, and ultimately, a deal cannot be done without breaching warranties (with significant legal ramifications).

Timing of IP due diligence

It’s important to protect before you disclose, or at least consider what you should and should not publish (e.g. whether to make all source code available alongside your publication or keep it as proprietary IP that can be licenced from your University).

NOTE: Publication includes any public disclosure or discussion (in any form) of the IP e.g. at conferences, meetings, in pre-prints, journals, blog posts or conversations in any public forums.

Avoid unnecessary speculation in publications about future uses of concepts of a discovery as it will be a public disclosure and jeopardise future arising IP based on the concept.

There are different time-points when it’s important/advisable to update your IP due diligence, although the earlier the better, to save time, resources and prevent mistakes. It is recommended to carry out and refresh your IP due diligence periodically, it is never static whilst research is ongoing.

- During research funding applications, if requested by the funder.

- At the point of IP disclosure, once something tangible has arisen from research.

- In advance of licensing, as the licensee will most certainly investigate this prior to committing.

This should be an ongoing practice, particularly to ensure that current IP covers current products or inventions. It is not unusual for products and processes to change in development and for early patents to no longer be relevant.

Conducting IP due diligence

You’ll need to briefly describe the IP (product or process) to your TTO (including any confidential know-how/material) and clarify any third-party materials (that you have brought in to enhance or merge with your IP e.g. open-source software code, parent cell line or creative outputs you are responding to) or public domain materials, (even public domain materials usually comes with T+Cs).

Describe the innovative part: what problem has been solved and how you have solved it (that no one else, to your knowledge, has disclosed). If the invention contains a component from a third party, this doesn't exclude you from its use as a whole system. However, the TTO needs to note what the originator declares about origin and rights to use materials.

Note: TTO may need to explore the details further, as the innovation description process evolves.

Ownership

Identify creators, originators and contributors to the IP.

Ownership of IP

- Your employer (the University) generally owns the outputs of your academic research unless there is a contract that says otherwise. This is not negotiable and is standard practice throughout all sectors of industry and public sector life, under UK employment law. There may be exceptions, e.g. copyright in research publications can be owned by the researcher, and transfers to the journal upon acceptance of a manuscript.

- Ownership determines who can use the research output for any purpose (research, teaching or commercial application). You need the University’s permission to use the research output for commercial purposes, usually in the form of a licence. Ask your TTO for advice.

- It is a common misunderstanding that IP, such as a patent, prevents research by others. This is normally avoided in many countries, such as the UK/EU, by the “research use exemption”, where a patented invention can be used for research purposes without permission from the patent owner.

- Is your research IP based upon any ‘building blocks’ of other research or existing technology? This helps the TTO to ascertain if a licence to this third party (background IP) is required, as it may present a freedom to operate (‘FTO’) concern down the line.

- Grant Funder T&Cs or Collaboration Agreements under which the IP has been generated. (TTO to clarify this). IP ownership can sometimes reside with a collaborating institution or external partner, based on funding terms, even if you have done most of the work (e.g. some NIHR-funded research grants or SBRIs).

- When leaving the University: it's important to know which elements of your work contain IP owned by the University when you leave an institution and where any agreements need to be drawn up. There is a difference between your personal knowledge and your curated expert know-how (confidential know-how and data produced whilst you worked at the University), e.g. for use in technical consultancy. You need to seek advice to understand what you can do outside the University and in what instances you will need University consent.

Contributors to the IP

You’ll need to advise the TTO of the following information:

- Under what project(s) and funding sources did the IP arise?

- Identify and list those persons who invented/created the IP. Please provide full names, positions (e.g. employee, PhD student/UG student, visiting academic, etc.), nationality, residency and the nature of their contribution, including:

- If University staff solely invented/created it;

- If any University students were involved in the Project per se (i.e. involved in the generation of the IP but not noted above as an originator/creator;

- If any other University persons were involved in the generation of the IP (but not noted above as an originator/creator);

- If any third parties invented or created IP, or were involved in the project.

An originator (or inventor in patent nomenclature) is someone who has made an intellectual contribution to a novel idea. Someone is not an originator if they provided input into what criteria a solution must meet, or feedback on the development of a discovery (without ideas on how to implement the solution). Equally, a person who is merely directed to do work is not an originator. These people may fall into the category of contributors. A risk here is that the omission of a legitimate inventor, or inclusion of a non-inventor, can invalidate a patent.

All originators, creators and contributors will need to agree on their percentage contribution. This should be in writing and disclosed early to the TTO by filling in and signing an IP Originator’s Agreement. This is preparation for any shareholder agreement and internal revenue sharing policies at your University.

Note: Joint owners have equal and undivided ownership (all originators are considered equal under the law). If patent claims are amended to exclude work done by certain originators, then they should be removed as originators, particularly for the US filing.

Any encumbrances?

Determine whether funders have ownership rights or revenue sharing expectations. This feeds into warranties that investors and licensees will expect, hence why this is so important to understand at this early stage, before commercialisation.

Encumbrances on the disclosed IP

Has the IP you have disclosed to the TTO for due diligence been introduced to subsequent research projects (e.g. as background IP for new collaborations or used following publication by practitioners in your field)?

If yes, have any third parties been granted rights to the IP in the relevant subsequent project? Is there any collaboration agreement with funder terms or an MTA?

Software (where applicable)

Please advise your TTO if there is:

- Third party code incorporated in your software

- Code in your software which has been released by you or a third party under specific licence terms (e.g. open-source software)

- Code stored in the cloud or a server, etc. Who has access and how secure is this storage?

- Any libraries/database contents copied or substantial parts incorporated into your software?

- If yes - were these accessed with a licence?

- If yes – are they being used to train an AI model?

Open-Source Software or Free Software

Open-source software (OSS) is defined in terms of user freedom. That is, the freedom of users to use (and reuse) software without the need for additional consent. An open-source licence will never restrict the use of software; however, they do place some obligations on how modified software is redistributed.

Open-source software offers benefits, such as cost savings, customisation, transparency, and community-driven innovation. However, risks include potential security vulnerabilities, lack of dedicated support, compatibility issues, and possible licensing complexities. Proper evaluation and management can mitigate risks while maximising benefits.

There are two main categories of open-source licenses:

Copyleft licence: These licences ensure that derivative works remain open source. If you distribute modified versions of the software, you must do so under the same licence, maintaining the freedom of the software. e.g. GPL, LGPL, AGPL

Permissive licence:These licences are flexible and allow for the software to be used, modified, and redistributed with minimal restrictions. They are business-friendly and allow proprietary use. e.g. MIT, BSD, ASL

National Security and Investment Act 2021

The National Security and Investment Act 2021 (NSIA) allows the UK government to scrutinise and intervene in certain acquisitions made by anyone, including businesses and investors, that could harm the UK’s national security.

Should rights in an invention (in 17 sensitive areas of the economy covered under the NSIA, called ‘notifiable acquisitions’) be acquired by any entities, then (subject to certain criteria) the University has an obligation to notify the UK government. So, it’s important to know upfront if the innovation/idea/IP lies within the scope of the NSIA.

Please confirm if your innovation sits within any of the 17 areas listed in the NSIA legislation (follow the link below)

NSIA Regulations details

If yes, then the TTO will need to assess whether it would be appropriate for the University to make a voluntary notification under the NSIA. This is significant; the penalties for getting this wrong can result (in the extreme) in imprisonment. For this reason, the TTO will often request legal assistance in this area.

Export Control

Export controls can apply to the digital or physical export of any goods, data, technology, documents, materials or software from a destination within the UK to a destination outside the UK. Export controls are needed for a variety of reasons, including national security and international treaty obligations. In the UK, the control of strategic goods and technology is undertaken by the Export Control Joint Unit.

Export control rules do not just apply to commercial export but to all kinds of academic activity, including teaching and research. This can extend to academic fieldwork, virtual teaching to students abroad, and presentations at international conferences. The TTO will assess whether the activity will require an export licence, and if so, manage this on your behalf or through other colleagues.

Consider if the University may be exporting any goods and technology, or know-how and data outside of the UK, either now or as part of a downstream commercialisation strategy?

Ethical Governance

Good research is underpinned by a culture of integrity and good governance. Research ethics are principles that guide how you should work with:

- research participants, their data or tissue

- artefacts that have a cultural or historical context

- other researchers and colleagues

- users of your research

- others you engage with (offline and on/analogue or digital)

Research ethics are part of good governance and apply to all research conducted at the University. Failure to have an appropriate approval may be seen as misconduct.

Advise your TTO of any ethics or consent which is pending or was granted during the research.

Your TTO or research governance team can provide a contact point within the University’s relevant ethics team (i.e. for verification of appropriate ethics and consents being in place).

Resources

Explore our ‘how-to’ guides and legal agreement resources to streamline spin-out company formation, help find investment and optimise licensing transactions.

PLAYBOOKS

How to guides explaining the ‘why’ and the ‘how’ of the commercial deal, ensuring an efficient process.

View PlaybooksTEMPLATES

A suite of lawyer-reviewed, legal Templates for everyone in the commercial deal to use.

View TemplatesCHECKLISTS

Useful Checklists to ensure that all critical elements are considered in the commercial deal.

View Checklist