RESOURCES | PLAYBOOK

Intellectual property due diligence playbook (TTO)

This playbook helps ensure that the University can commercialise intellectual property (IP) from academic research, while also meeting the legal requirements. ‘IP’ here refers to a product or a process.

IP due diligence undertaken at the earliest stages of discovery helps ascertain whether the IP identified or disclosed by an inventor can be commercialised - typically either by spinning out a new company and granting it rights to the IP, or granting rights to the IP to an existing company via licensing, and so on.

This playbook is intended for technology transfer office (TTO) staff and academic researchers across all disciplines (SHAPE and STEM).

Key Points / Executive Summary

- Publishing or disclosing your research outputs can have knock-on effects for the commercialisation of your research. There are some critical aspects you need to consider and discuss with your TTO before you place anything in the public domain.

- IP can be protected and registered in a timely manner by your TTO, with no (or minimal) delay to publication or public disclosure.

- IP is owned by your employer (unless a contract says otherwise) and this ownership does not move when you change employment.

- In a competitive field others may have existing IP, this does not necessarily exclude new related IP if it has a competitive advantage, your TTO will be able to map out the position.

- The research use exemption normally allows others to use for research purposes, thus generally patents do not limit research in a particular field (though in certain countries this exemption may be less defined).

- Understand any encumbrances on IP (such as joint ownership or needing funder consent to commercialise) and revenue sharing expectations, so that you are aware of as these matters impinge on the commercialisation process

The Deal Readiness Toolkit

A short video introduction to the benefits of using the Deal Readiness Toolkit, covering a patent attorney perspective with insights from the Southampton TTO office.

What is IP?

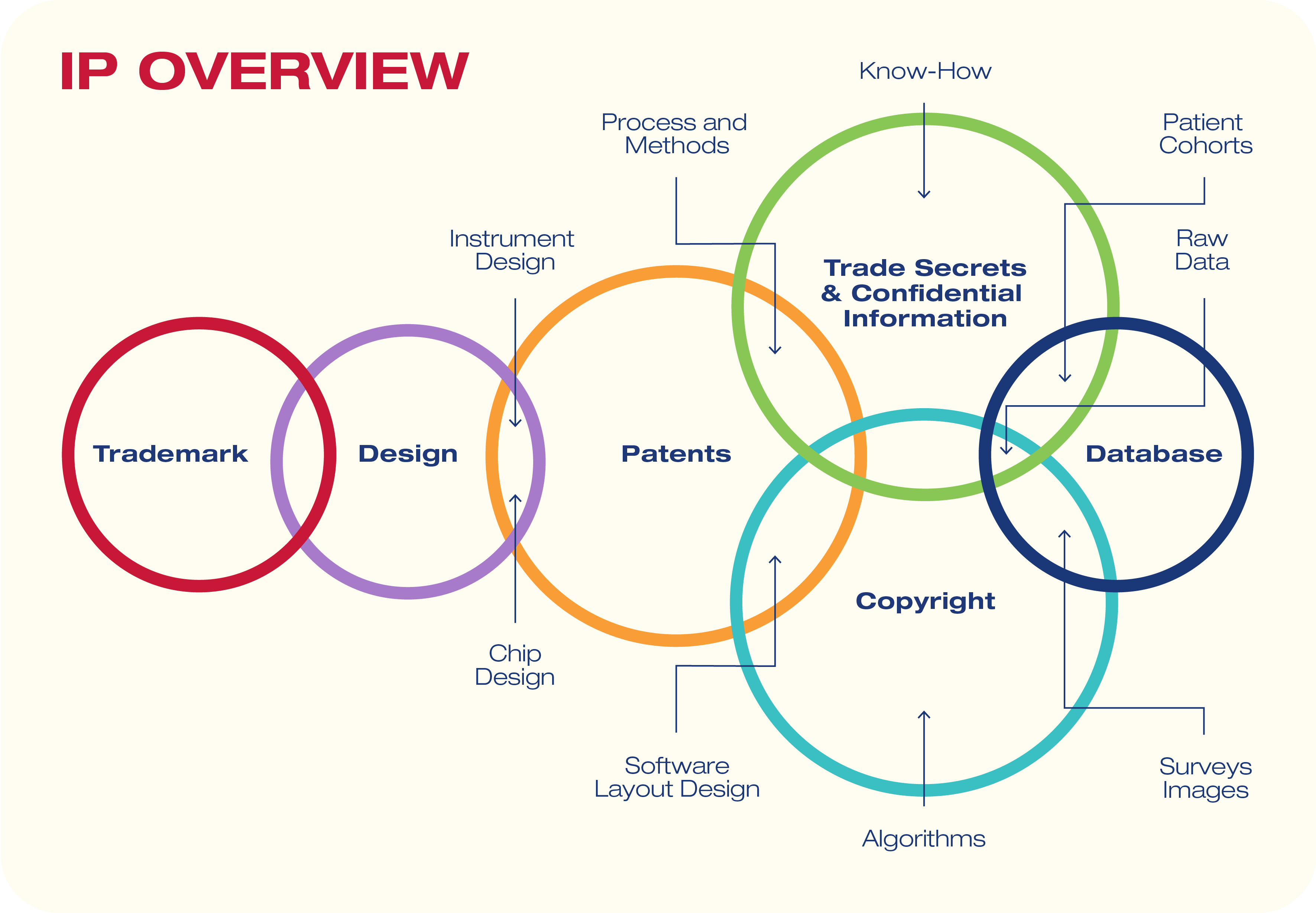

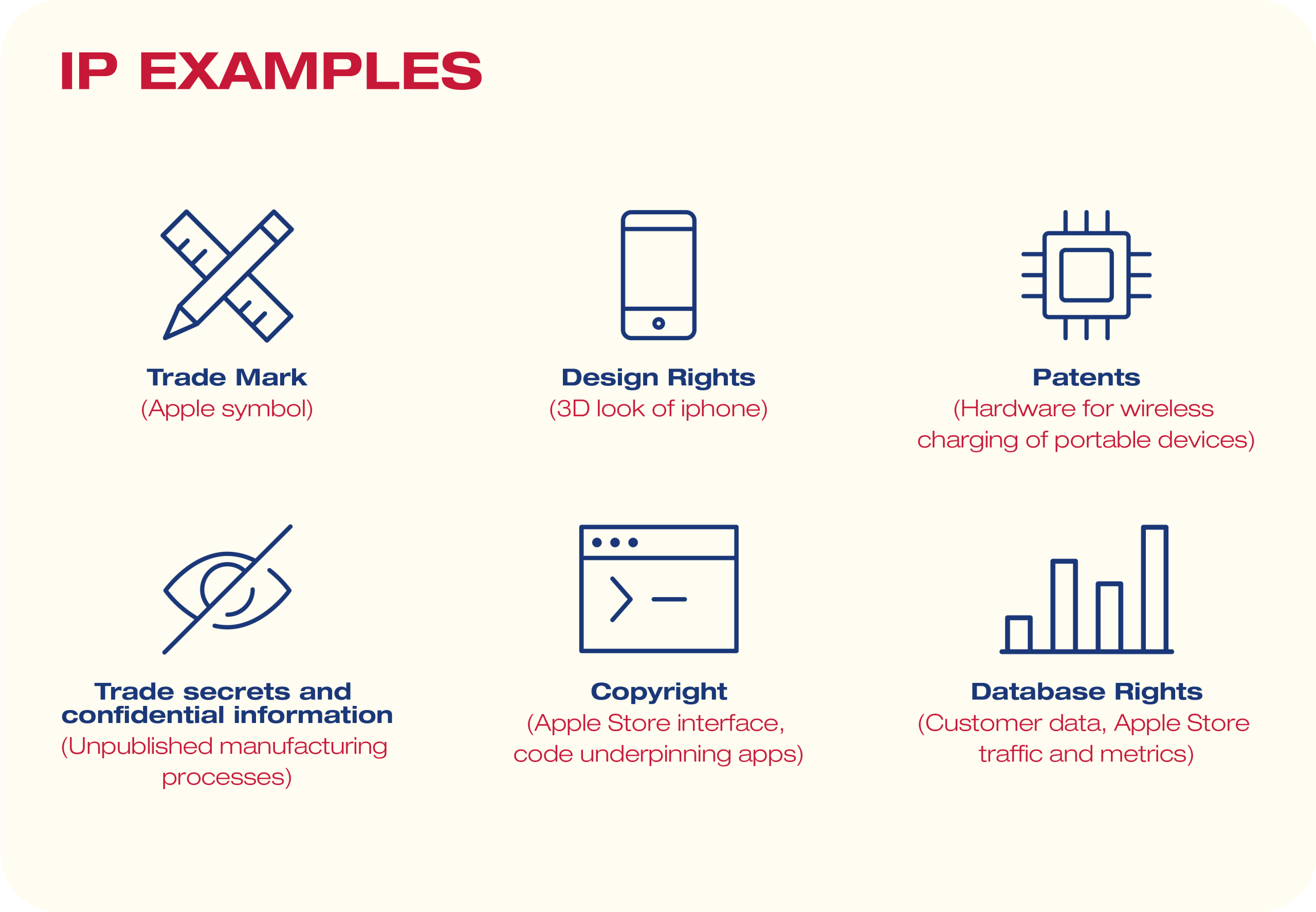

Intellectual property or ‘IP’ covers a product or process and falls into any of the six types of creative output developed within the University (see the diagram below).

[Used with permission of copyright owner, see examples below:]

Exploitable IP takes various forms. IP can be made available (by means of an agreed contract, typically a licence agreement) to others in a variety of ways, such as a freely available resource (e.g. some copyrighted materials or open-source software); or traded under a commercial licence (e.g. a patent claiming a new technology and its associated know-how), to a newly incorporated spin-out or an established entity.

What is IP due diligence?

The “innovation” needs to be assessed for its commercial viability, or its social value (if considering a social enterprise, in terms of its balance of an ESG profile). To do so, the University's TTO (or Research Innovation Services or Enterprise Division) needs to determine whether it is useful and whether there is a market for the innovation. Key questions to be answered at this stage are:

- What real-world problem does the invention solve?

- Is there a significant-sized market, and what is the value of the market?

- What would it take to commercialise (e.g. time, effort, cost, regulatory requirements, etc.)?

- Has the problem already been solved by someone else?

- Who are the potential licensees and customer base?

Its protectability needs to be ascertained: is the innovation novel and inventive, what is the ownership of the IP and are there any obvious encumbrances or (by undertaking a brief, targeted, novelty search). A more detailed freedom to operate (FTO) search can be undertaken at a later stage, usually in cooperation with a patent attorney, and if a commercially viable product has been determined. This is critical in enabling downstream commercialisation activities.

Why do we do IP due diligence?

Even if the main motivation for the IP is to obtain grant funding, the protection of a commercially viable and useful product or process needs to be demonstrated. If there is a commercial strategy, IP ownership needs to be concisely articulated prior to proceeding with protection for the innovation. If done successfully, TTO and academics could identify areas of future IP and new developments (both products and/or markets) to leverage more grant funding.

Considerations for the Technology Transfer Officer

Ascertaining ownership and encumbrances means working with inventors of the innovation to clarify:

(i) Who had a hand in creating the IP: in their research group and by any other contributors. Determine inventorship, legally defined as the person (or persons) that formulated the inventive concept.

(ii) IP ownership rights: An inventor’s employer is usually the owner, but collaborators, partners and funders may also have rights. TTOs need to review funder terms around ownership, collaborators’ or licensees' rights and revenue-sharing expectations.

(iii) If the IP is a material or software code, is it: wholly owned by the University OR from pre-existing public domain material with T&Cs OR from a collaborator OR under a Material Transfer Agreement? TTOs check agreements for such third-party rights and encumbrances.

(iv) Rights to the IP granted in any commercial transaction require that the University must give certain legal assurances (such as warranties) over the ownership and protection of the IP.

Example questions to ask inventor(s):

- When do you plan to publish data/research results related to the invention?

- What is the inventive concept, and what date was it formulated?

- Is there documentary evidence (e.g. lab book)? This may become important if a third party challenges the IP.

- Do you know of any other research groups or businesses conducting research into this tech?

- Are there any public disclosures (non-confidential) by you or other people that anticipate the invention or are material to the IP?

- How was this research funded?

- Who had input in creating the IP, and were there any supplemental contributors you wish to acknowledge?

- Following a landscape search into the invention: look at the listed patents and “prior art” and consider matching tech/related tech, etc. Are there any overlaps with the invention? Is there a non-obvious improvement for the invention? What is the lifetime and prosecution status for overlapping patents? Are they in relevant countries? What can you learn from the examiner’s objections and searches?

- Remember, if IP becomes valuable and captures market share from a competitor, then often the competitor will make a legal challenge attacking what they perceive to be the weakest points in the IP. A thorough paper trail of the diligence will be important.

Disclosure of IP by an academic for review of commercialisation potential

- What type of IP – Patent, Trademark, Material, Knowhow, Copyright and Designs.

- Any relevant patent application numbers.

- Confirmation whether the patent application has been filed.

- What competitive advantage does it create in the market?

Other considerations

You should document all disclosures received by the TTO, so that reporting can be done (e.g. HEBCIS) and year-on-year comparisons made (e.g. to review people and budget resourcing in your team).

Ownership

Identify creators, originators and contributors to the IP.

Ownership of IP

Clarify ownership of the innovation/idea/IP:

Does it solely belong to the University based on inventive contribution?

- If YES, please gather all the names and positions (e.g. employee, PhD student/undergraduate student, visiting academic, etc.) and nationality & residency of those University persons who invented/created the IP. This is legally defined at UKIPO. Patents: Manual of Patent Practice - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

- If NO, please provide all names of third parties who invented/created the IP – including: personal names and company/institution names, addresses and other contact details.

If there is University ownership, ensure assignments to the University have been obtained from all known originators/creators.

Understand the basis for the University being the party to commercialise (e.g. taking assignment from co-originator(s), co-creator(s) or collaborating institutions).

- Were there any additional contributors to the innovation/idea/IP who are not deemed to have had inventive contribution but were key in making the innovation tangible?

Clarify if the innovation/idea/IP has come out of work or research associated with a PROJECT or GRANT.

- If YES, have the relevant project agreement (e.g. collaboration, studentship, material transfer) and any funder terms been checked to make sure that the terms do not grant any third-party ownership rights?

- If NO, ensure you can trace the source of internal or departmental funds, for downstream due diligence as part of any commercialisation deal.

Contribution to the IP

Determine if any agreements have been made on originators’ percentage contribution to the innovation/idea/IP.

Document inventive contribution and percentage accordingly, to comply with any originator revenue sharing process within the University.

Ensure to check any PhD studentship agreement terms on ownership and licence rights to the funder and student.

Check that this is in agreement with all the originators listed, to prevent disputes once a deal materialises.

Determine if any companies, other institutions or third parties were involved in the project or creation of the IP.

An originator (or inventor in patent nomenclature) is someone who has made an intellectual contribution to a novel idea. Someone is not an originator if they provided input into what criteria a solution must meet, or feedback on the development of a discovery (without ideas on how to implement the solution).

Equally, a person who is merely directed to do work is not an originator. These people may fall into the category of contributors. A risk here is that the omission of a legitimate inventor, or inclusion of a non-inventor, can invalidate a patent.

Remember, jointly owned IP with a collaborating institution is generally not preferred by a potential licensee as it complicates liability.

If anything goes wrong and jointly owned IP is treated differently in different territories, particularly with respect to the owner’s ability to use and license, then permissions from the joint owner may be required.

Any encumbrances?

Determine whether funders have ownership rights or revenue sharing expectations. This feeds into warranties that investors and licensees will expect, hence why this is so important to understand at this early stage, before commercialisation.

Encumbrances on the disclosed IP

Review any relevant project agreement or funder terms for any automatic licences (R&D and/or commercial) and for any ‘live’ option to licence rights and the like, including any funder rights to input/sign off on future commercial agreements (e.g. commonplace for NIHR and Wellcome Trust).

If any such (option to) licence rights have been granted to third parties, ensure you understand the details and any encumbrance this may present in downstream commercialisation activities.

For funder rights, ensure you approach the consent process in sufficient time, whilst a deal is being worked up!

Has the academic(s) confirmed that they haven’t promised rights in the IP to anyone else?

Software (where applicable)

Determine the nature and source of any code used in the proposed innovation software products, including:

- Any third-party code

- Any open-source software licenses

- Code already released under licence

- Incorporation of libraries or databases

If any of the above are incorporated in the innovation, what is the status of licence agreements for their use?

Where is the code stored and who has access to the code – how secure is the repository?

Open-Source Software or Free Software

Open-source software (OSS) is defined in terms of user freedom. That is, the freedom of users to use (and reuse) software without the need for additional consent. An open-source licence will never restrict the use of software; however, they do place some obligations on how modified software is redistributed.

Open-source software offers benefits, such as cost savings, customisation, transparency, and community-driven innovation. However, risks include potential security vulnerabilities, lack of dedicated support, compatibility issues, and possible licensing complexities. Proper evaluation and management can mitigate risks while maximising benefits.

There are two main categories of open-source licenses:

Copyleft licence: These licences ensure that derivative works remain open source. If you distribute modified versions of the software, you must do so under the same licence, maintaining the freedom of the software. e.g. GPL, LGPL, AGPL

Permissive licence: These licences are flexible and allow for the software to be used, modified, and redistributed with minimal restrictions. They are business-friendly and allow proprietary use. e.g. MIT, BSD, ASL

National Security and Investment Act 2021

The National Security and Investment Act 2021 (NSIA) allows the UK government to scrutinise and intervene in certain acquisitions made by anyone, including businesses and investors, that could harm the UK’s national security.

Should rights in an invention (in 17 sensitive areas of the economy covered under the NSIA, called ‘notifiable acquisitions’) be acquired by any entities, then (subject to certain criteria) the University has an obligation to notify the UK government. So, it’s important to know upfront if the innovation/idea/IP lies within the scope of the Act.

Could the IP be used to carry out activities in any of the 17 sensitive sectors identified by the UK Government?

NSIA Regulations details

Check with the originator if the innovation/idea/IP falls under any of the sensitive areas, and consider whether to make a voluntary notification under the NSIA.

Export Control

Export controls can apply to the digital or physical export of any goods, data, technology, documents, materials or software from a destination within the UK to a destination outside the UK. Export controls are needed for a variety of reasons, including national security and international treaty obligations. In the UK, the control of strategic goods and technology is undertaken by the Export Control Joint Unit.

Export control rules do not just apply to commercial export but to all kinds of academic activity, including teaching and research. This can extend to academic fieldwork, virtual teaching to students abroad, and presentations at international conferences. The TTO will assess whether the activity will require an export licence, and if so, manage this on your behalf or through other colleagues.

Will the University be exporting any goods, technology or know-how outside of the UK?

Please refer to the University’s Export Control Policy or specialist team for advice on the latest procedure.

Ethical Governance

Good research is underpinned by a culture of integrity and good governance. Research ethics are principles that guide how you should work with:

- research participants, their data or tissue

- artefacts that have a cultural or historical context

- other researchers and colleagues

- users of your research

- others you engage with (offline and on/analogue or digital)

Research ethics are part of good governance and apply to all research conducted at the University. Failure to have an appropriate approval may be seen as misconduct.

Check to see if the relevant ethics approvals are in place for the data incorporated into the IP.

Consent from any public or patient engagement in the research may be only partially granted (e.g. only for research and not commercial purposes), so where required, try to ensure commercial rights are secured during the research phase and well in advance of embarking on commercialisation activities.

Resources

Explore our ‘how-to’ guides and legal agreement resources to streamline spin-out company formation, help find investment and optimise licensing transactions.

PLAYBOOKS

How to guides explaining the ‘why’ and the ‘how’ of the commercial deal, ensuring an efficient process.

View PlaybooksTEMPLATES

A suite of lawyer-reviewed, legal Templates for everyone in the commercial deal to use.

View TemplatesCHECKLISTS

Useful Checklists to ensure that all critical elements are considered in the commercial deal.

View Checklist